Recap

We’ve covered the basics in Part 1 – how the human mind is not used to dealing with random numbers, how large numbers are used to even out probabilities, and we introduced the normal distribution. Let’s continue:

The Law of Inevitability

One out of all possible outcomes must occur.

Throwing a die must result with the number 1 to 6. However, this law becomes more useful when dealing with tiny probabilities, such as the lottery or the stock market.

Take this example: I pretend to be a stock-market analyst and I am mailing people my predictions for a certain stock in the stock market. There are two outcomes – it can either rise or fall. Let’s start with 1024 people. I tell half of them that the stock price will rise and the other half that the price will fall. If the stock price does rise, I would continue to stay in correspondence with the 512 who were told correctly that the price would rise – and ignore the 512 whom I gave the wrong prediction to. I would repeat this for 10 weeks.

Regardless of whatever happens to the price (rise or fall) there will always exist a group that was given the correct predictions so far – it’s just that the group gets halved and halved farther. At the end of 10 weeks, there will be left a group of one person who would have been told the correct prediction every time. They might assume I am a soothsayer able to predict the future, or that person just happened to be 1/1024 up/down configurations that turned out to be correct.

Law of Truly Large Numbers

With a large enough number of opportunities N, any event (regardless of how small its probability) has a probability of occurring in an N independent trials that tends towards 1.

Suppose I have a random number generator that generates numbers between 1-1000. If I run the random number generator 10,000 times the probability that a certain number (481) in that range does not show up is equal to 0.999^10000. (999/1000 choices)=0.999.

The probability of never getting 481 at all in 10,000 trials is equal to 0.0000451, or a 1 in 22173 chance. And 10,000 trials isn’t considered a truly large number.

Take the 2009 Bulgarian Lottery for an example. The lottery made national headlines when the winning numbers were drawn, and they turned out to be the exact same winning numbers as last week’s – 4, 15, 23, 24, 35 and 42. 1

This lottery was a 6/49 lottery, where a player chooses six numbers from 1-49 with no duplicates. If the numbers raffled matches the player’s number (regardless of order) the player wins the jackpot. There would be 49C6 combinations, or 13,983,816 possible choices for numbers.

If the lottery only ran twice, there would only be one possible pair (2C2 = 1),(1&2) that had the same numbers so the probability of a repeat same number set being chosen would be 1 in 13,983,816.

Keep in mind we are talking about repeated numbers based on the history of all numbers of the lottery, and not two consecutive correct draws (otherwise that probability would be the same as the one mentioned in the top paragraph.)

What if the lottery had been held 1000 times? That would mean 1000 draws of the numbers. This translates to 1000C2, or 499,500 possible pairs that could be found. (1&2, 1&3, 1&4…) The probability having two repeated draws would be (1/13,983,816*499,500) ≈ 0.036. Sounds plausible.

If the number of possible pairs exceeded the 13,983,816, you can guarantee that there would be a repeated draw eventually (once you exhaust the entire set of configurations the next draw will match any configuration that exists in the set).

Working backwards, once the lottery is held 4404 times, it is more than half likely that any two draws will match. At 5290 times, it is guaranteed any two draws will match. If a lottery is held bi-weekly, it would take 51 years for a guaranteed match – and we see the pattern here! The Bulgarian lottery held almost biweekly and was 52 years old at the time, which does line up with the 51 years value we calculated – accounting for some weeks where lotteries were not held such as public holidays.

The Bulgarian lottery was unique so that two consecutive sets of numbers were drawn – a coincidence of 1 in 13,983,816. But we need to take into account for all the countries around the world holding several many lotteries at once. Two consecutive sets of numbers were also drawn in North Carolina in 2007.

The Law of Truly Large Numbers goes to show that occurrence with small probabilities will happen, given enough possibilities.

However, this law is the reason for uncertainties in science research that are time-consuming to deal with– for example, the search for the Higgs boson particle. It involves lots of gleaning through data to detect evidence of the Higgs boson phenomenon which would be manifested in high numbers of particle count at a certain mass. However, we do not know if they were caused purely by chance or by the Higgs boson.

The Law of Selection

Humans tend to hold on to things that fit their narrative, and marginalise events that oppose it. This is such the case relating to psychic mediums and prophecies. Take Jeane Dixon for example, a famous psychic who was a personal advisor to Nancy and Ronald Reagan. She made several correct predictions such as a Democrat winning the 1960s U.S. presidential election and the assassination of the president in 1960 – making her well-known for her prophetical ability. However this was balanced against her (lesser known but equally if not more outlandish) wrong predictions that the Soviet Union would be the first to send a man to the moon and the Second World War in 1958. People only remembered her for her correct predictions, which is the reason why Jeane had a cult following. It’s more statistically likely she made many ambiguous claims where only a portion turned out to be true.

(In January 2020, she predicted 2020 would end with an Armageddon. Let’s hope not.) [ Update 30 Nov 2021: I am still alive! ]

Regression to the Mean

Sir Francis Galton was a cousin of Charles Darwin and a scientist. He noted that characteristics extreme in their parents are likely to be less extreme in their children. For example, two very tall parents would typically produce children, although relatively tall, that were nearer to the average than their parents. Similarly, two shorter parents were more likely to produce children shorter than average but taller than them.

It was easy to assume that there was some sort of biological mechanism pulling the offspring’s height back to the average, but this was purely the law of selection manifesting itself, resulting in the regression to the mean.

Let’s ask a group of 3600 people to throw a fair 6-sided die. You would expect about 600 of them to get a one, 600 people to get a two, etc…and 600 of them to get a six.

Now, let’s focus on the 600 who got a six. Get the 600 people to throw the dice again, and we would expect that only 100 of them would get a six on the second try.

If we focus on people who acquired six, which is above the average (3.5), it’s more likely the next number they throw will be closer to the average, or less than six. The opposite is seen for numbers thrown below the average – it is more likely the next value that is thrown is closer to the average, or larger than the previous throw.

This holds true as the law of large numbers is at work here – keep asking them to throw the numbers over time and the average of their throws will tend to 3.5.

The law of selection is also to blame for this phenomenon because Galton noticed that comparisons were being made with the taller and shorter parents on the more extreme ends of the spectrum.

To further elaborate, we are not dismissing that a person’s height is determined by chance alone; height is dependant on genetic and environmental factors. For sake of explanation, genetics determine height to a certain range.

This is why a pair of tall parents are perceived tall because they reached close to their maximum height in the height range.

Their child will inherit their genetics that account for a certain range in height – and it will simply be up to chance/environmental factors to decide whether the child occupies the upper or lower part of the height range.

Selection/Publication Bias

Scientific journals are more preferable to be published when they successfully show a phenomenon, instead of those that fail to show one.

Editors prefer to publish journals that show things work.

Selection bias is also seen when scientists are inclined to prove that something works – for example, whether a drug can successfully treat a sample of patients.

If placebos are not accounted for, even if patients get better purely by chance, the drug trial will appear to be effective, even if it is not.

Because of publication bias, not all discoveries/studies are valid, and hence after a certain period findings from newer studies will refute or conflict with their older counterparts.

A group of scientific studies once studied links between whether eating breakfast or not led to weight gain. The general consensus was that eating breakfast in the morning would not influence weight gain, although most of the studies were funded and published by food manufacturing companies 2 – and were conducted without double blinding 3. Double blinding means that every participant and the scientist who collects the data are unaware of treatment procedures and hypotheses to minimise bias.

Another effect of the Law of Selection bias is the dropout bias in regards to clinical drug trials. It is not uncommon for patients to drop out of a clinical study. Sometimes patients drop out of the trials because they are starting to feel better early on and do not wish to stay in the study any longer. Their cases may not be tabulated, and as a result, may make the drug seem like it is not effective.

The Probability Lever

On October 19, 1987, the S&P 500 stock price fell by 22.6% That days was also called Black Monday, the largest percentage drop in all history of the American Stock Market, that sparked fears of worldwide economic instability.

Sebastian Mallaby claimed that the probability of the plunge was 1 in 10^160. “In terms of the normal probability distribution, to put that probability into perspective, it meant that an event such as the crash would not be anticipated to occur even if the stock market were to remain open for twenty billion years, the upper end of the expected duration of the universe, or even if it were to be reopened for further sessions of twenty billion years following each of twenty successive big bangs.” 4

Borel’s Law states that we should not see events as improbable as Mallaby’s example. Why did it occur? David J. Hand, the author fo the Improbability Principle, calls the hidden cause “the law of the probability lever.” 5

A slight change in circumstances can have a huge impact on probabilities.

Keep in mind the quote of Mallaby’s takes the normal distribution into account. When scientific theory does not match what is observed, there could be a few causes – either it was problems with data (measurement errors), or the theory/assumptions are not mistaken.

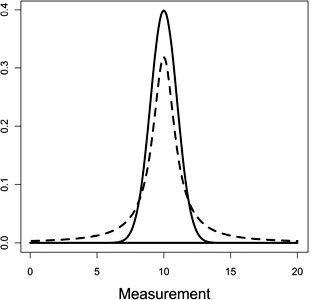

The normal distribution has very nice mathematical probabilities, making theories and predictions easy to calculate. However, measurements often follow the normal distribution to an approximate extent.

(Photo taken from The Improbability Principle by David J. Hand)

The book The Improbability Principle introduces another distribution: The Cauchy distribution. Assume we have a children’s IQ test, and scoring 20 and above would be considered a ‘genius’ score.

The probability of scoring above 20 using the normal distribution, is 1.3*10^23, which is so small that Borel’s Law applies, and we do not expect this to happen.

However, the probability of scoring above 20 using the Cauchy distribution is 1 in 31, which is much more likely. 3 out of every 100 children would score above 20, making this a score that shouldn’t really be called a ‘genius’ score.

This shows that a slight change to the shape of distribution can greatly impact probabilities that are insignificant to the point that they might happen in everyday life.

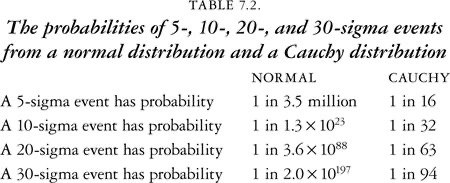

Another way to name events is by using the sigma – for example, a 5-sigma event is the probability of getting a value 5 standard deviations smaller/larger than the mean(where the distribution curve peaks). Now compare the table below of probabilities in the normal and cauchy distributions.

(Photo taken from The Improbability Principle by David J. Hand)

The probability lever is related to chaos and the butterfly effect. Let’s take an example here.

Atoms are very, very tiny, and they collide extremely quickly. A gas molecule collides every 1/50,00,000 seconds on average – 5 billion collisions per second. Removing one electron rom the edge of the universe could affect how atoms in space collide, all the way to Earth and Earth’s atmosphere, altering how oxygen molecules move in the air would completely change the path of oxygen molecules in the air you breathe after just 1/100,000,000 of a second.

Chaos, as described earlier, is extremely sensitive to initial conditions. And it is impossible to get the initial conditions exactly correct (it involves infinite decimal places of accuracy).

The double pendulum is another example of a chaotic system:

(Photo taken from fouriestseries.tumblr.com)

Changing the initial conditions a tiny bit will greatly alter the path and movement. It will be impossible to replicate the path of a double pendulum as the angle is continous (infinite decimal places of accuracy), although it is deterministic– you can theoretically predict the movement of the pendulumn from a given initial condition.

My Probability or Yours?

Major Walter Summerford was struck by lightning thrice over twelve years of his life. His gravestone was struck in 1936, four years after his death.

The probability of being struck by lightning is 1 in 700,000. To be struck thrice in your lifetime and once more on your gravestone is virtually zero chance – but not for Summerford. He was an outdoor person – and every time he was struck by lightning he was outside walking around during a thunderstorm. The probability of him getting struck would massively increase if he was outdoors, compared to most people who spend a majority of time indoors. Couple that with a 2-billion population(at the time), there would be many people happening to be outside during a thunderstorm.

At the time of writing, there are 20,827,622 cases of the coronavirus and 747,584 deaths from coronavirus. As a college student who spends most of my summer indoors, does my probability of dying from coronavirus equal the deaths over earth’s population? (747,584/7,594,000,000) ≈ 1 in 10158.

Most probably not. The probability of dying from coronavirus would be greatly increased in those who spend their times outdoors (essential workers), the elderly, weaker patients with an underlying health conditions 6, and in the citizens of countries with less access to advanced health care. In a coronavirus-free country such as Montenegro, the probability would be almost zero.

There is a joke where your temperature will be the average, if your feet are in an oven and your head is in a freezer.

Here’s another example: 8% of the world’s population has blue eyes. Does that mean I have a 0.08 probabilty of being born with blue eyes? Not neccessarily. If you study biology, we know that that probability depends on your parents and the genes they carry.

The Law of Near Enough

Let’s say we are trying to guess the output of a 100-sided die. I choose 42, and the dice rolls 43.

“Oh no, I guessed so close!”

The probability of guessing right is 1 in 100. But since 42,43, and 44 are accepted as ‘correct’ or ‘close’, we’ve tripled our probability of surprise.

When we relax our criteria of definition, we greatly the probability of an apparent coincidence.

This complements the look-elsewhere effect in physics, where scientists search for “bumps“ – an excess number of observations that contain a particular value, to prove a certain phenomenon. If they find no “bumps” for a value, they will extend the search for any “bumps” at any values.

This dramatically increases the chance of finding a “bump”, because its criteria has been relaxed.

What about conspiracy theorists claiming that the Egyptians were enlightened by some supernatural nature to build the Great Pyramid of Giza at 29.9792458˚N, which happen to be the same digits of the speed of light, 299792458m/s.

The Law of Near Enough is in play here. First, we can place the decimal place anywhere, and the coordinates given are too specific– we only need 4 decimal places 29.9729˚N to roughly pinpoint the location of the pyramid (The law of selection applies here too). It does not help that the pyramid is extremely large and Egyptians did not use metres or latitude coordinates in 2500B.C!

Bayesianism, Science, and Religion

The Bayesian approach to believing things – eliminate the more improbable, and choose the outcome that is more probable. The great philosopher David Hume, wrote that “no testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous, than the fact which it endeavours to establish“. 7

Science is about looking for explanations – not necessarily the absolute truth. Science depends on probabilities – the collection of data and gaining greater and grater understanding. Conclusions are not set – truths are not absolute. This allows for science to improve its accuracy as we gain better data, allowing us compare probabilities and choose the outcome with the greatest likelihood.

Classical physics is one example – it was widely accepted in the scientific community before the 20th century. Classical physics, as implied by the name, had limits to its understanding – such as the photoelectric effect. Along came modern physics that revamped the paradigm, introducing uncertaintites and more particles at a subatomic level. Modern physics had an explanation for phenomena such as the quantum behaviour of light, that classical physics could not explain.

We replaced the older theories with the quantum-based theories that had better data to support it. And thus continues the cycle of self-improvement.

Conclusion

Why do very rare events occur in real life? With our recently gained paradigm, let’s sum things up:

We live in a chaotic universe; due to the universe’s quantum nature it is impossible to predict the future because we do not have complete knowledge of the present.

Correlation is not causation. As humans we find ourselves cherry-picking and focusing on ‘anomalous’ data that occurs by chance (Law of Near-Enough, Law of Selection, Publication Bias, Regression to the Mean) and concluding it as the truth.

The Law of Truly Large Numbers: There are 7.6 billion people on the Earth, endowed with 86,400 seconds a day. The Law of Inevitably states that with enough trials and opportunities, rare events will and do happen.

Probabilities for each person are different. This is why probabilities, on average, can be reduced when they could be greater in different people. Using the wrong distribution (e.g. Normal vs Cauchy) also disguises reasonable probabilities as virtually impossible.

The Probability Lever means that in certain circumstanes and in certain individuals, the probability of a rare event happening can wildly increase to the point where it is likely to happen.

-

Reuters, 2009. “Identical Lottery Draw Was Coincidence.” Reuters. 18-9-2009. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lottery/identical-lottery-draw-was-coincidence-idUSTRE58H4AM20090918 ↩︎

-

Kelloggs. “Best Start to the Day”, Kelloggs. Accessed 5-8-2020. https://www.kelloggs.com/en_US/nutrition/best-start-to-the-day.html ↩︎

-

BMJ. “Effect of breakfast on weight and energy intake: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials”, BMJ. 30-1-2019 https://www.bmj.com/content/364/bmj.l42 ↩︎

-

Sebastian Mallaby. In More Money Than God: Hedge Funds and the Making of a New Elite (New York: The Penguin Press, 2010), chapter 4. ↩︎

-

David J Hand, “The Law of the Probability Lever”. The Improbability Principle: Why Coincidences, Miracles, and Rare Events Happen Every Day(New York: Scientific American / Farrer, Straus and Giroux ,2015), chapter 7. ↩︎

-

WHO Europe. Statement – Older people are at highest risk from COVID-19, but all must act to prevent community spread, World Health Organisation. Published 2-4-2020, para 4-6. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/statements/statement-older-people-are-at-highest-risk-from-covid-19,-but-all-must-act-to-prevent-community-spread ↩︎

-

David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, 2nd ed. (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing 1993), 77. First published 1777. ↩︎