These posts are a series of my notes taken from the CS50AI course – Introduction to AI with Python. I have explained some areas for easier simplification.

At the heart of every algorithm lies its logic process, which forms the core part of decision making. The tricky part is, how do we program a computer to parse logic? In this explanation, we would want to give an algorithm a set of rules, and give it and a new rule. The algorithm has to tell us whether the new rule fits in with the old rules.

Prepositional Logic Basics

Let’s try and emulate a human’s thinking process. Take these three statements:

- If it didn’t rain, Harry visited Hagrid today.

- Harry visited Hagrid or Dumbledore today, but not both.

- It rained today.

Who did Harry visit? Well, we can infer some statements by combining several together. Take statements 1 and 3: It rained today, which means Harry did not visit Hagrid today.

Let’s apply that to statement 2, so Harry must have visited either Hagrid or Dumbledore. Since he did not visit Hagrid, so he should have visited Dumbledore.

Now, it’s time to bring computers in, using the form of prepositional logic. The system of prepositional logic involves symbols, sentences, and connectives.

Symbols are simply items that are assigned logic values. They are linked to each other via connectives to form sentences.

The statements numbered 1-3 are examples of sentences.

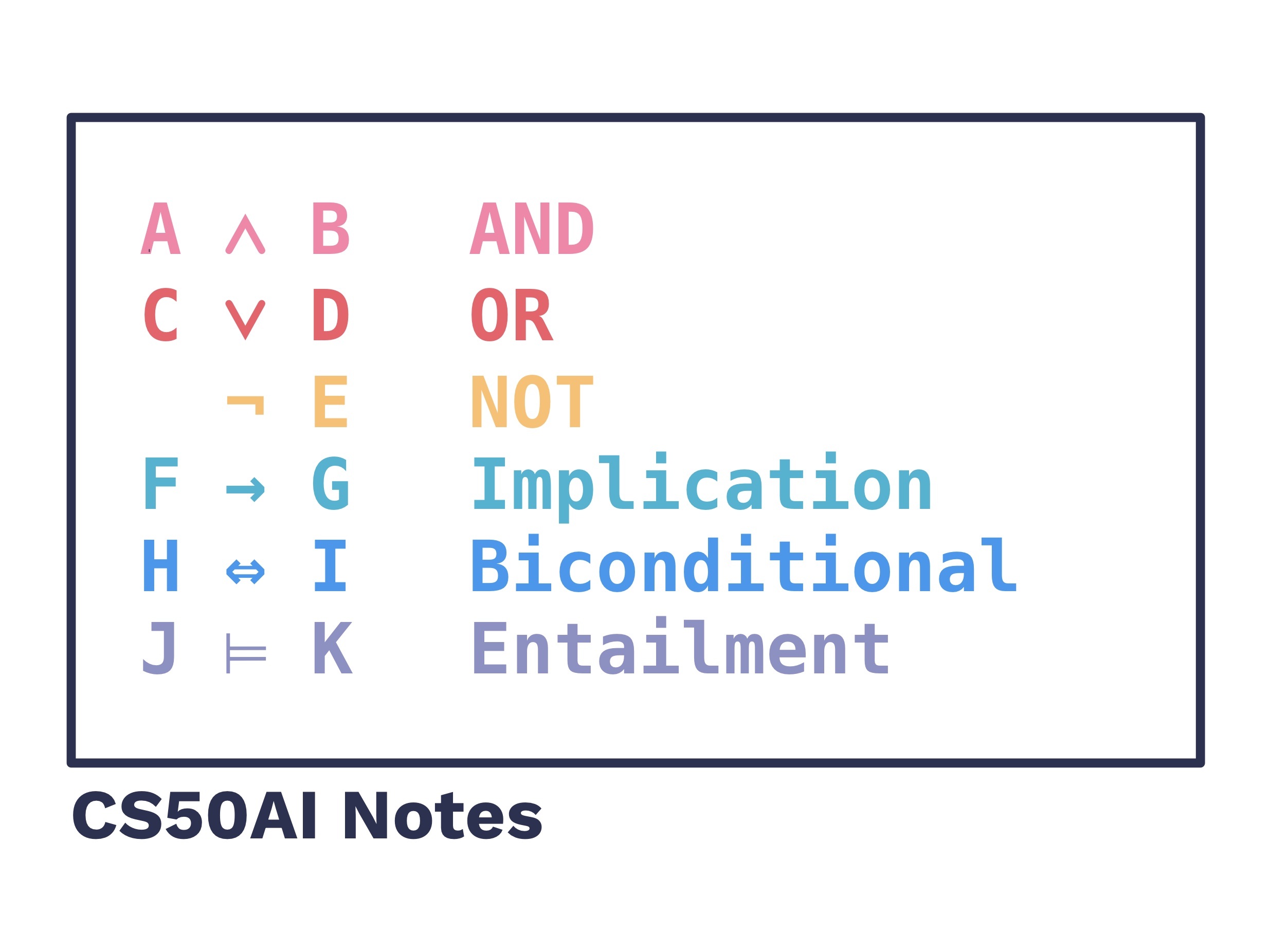

Here are some examples of connectives – first, we have the common And, Or, and Not connectives.

The And connective means both symbols have to be True to return True, and Or needs at least one True input to do the same.

| P | Q | P ˄ Q (AND) | P ˅ Q (OR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| false | false | false | false |

| false | true | false | true |

| true | false | false | true |

| true | true | true | true |

The Not connective returns the inverse of its input.

| P | ¬ P (NOT) |

|---|---|

| false | true |

| true | false |

The Implication connective is similar to an IF-THEN statement. If conditions P are met, then outcome Q will occur.

| P | Q | P → Q |

|---|---|---|

| false | false | true |

| false | true | true |

| true | false | false |

| true | true | true |

Example:

P: It did not rain today.

Q: Harry will go for a run today.

Given we know that P → Q, then we know that on rain-free days, Harry would surely go for a run. If it did not rain, but Harry did not go for a run, then the sentence P → Q is false, because the conditions met for P did not affect the outcome Q.

On days where it rained (P is false), it does not matter whether Harry went for a run or not, the sentence P → Q . This is the interesting part – because there is no contradiction between P and Q, True can be returned.

Pay attention to the bolded term as I’ll come back to that later.

A close relative is the Biconditional connective. It can be understood as an IF-THEN (AND ONLY IF) statement, meaning that one symbol implicates the other and vice versa. A logical equivalent would be (P → Q)^(Q → P).

| P | Q | P ⇔ Q |

|---|---|---|

| false | false | true |

| false | true | false |

| true | false | false |

| true | true | true |

Let’s look back at the previous example’s symbols.

P: It did not rain today.

Q: Harry will go for a run today.

Say we also know that P ⇔ Q, then we know that on rain-free days, Harry would surely go for a run, and whichever day Harry runs, we are 100% sure it did not rain.

In the case of P → Q, Harry might gone for a run in the rain. That would imply that the rain is not the sole cause of Harry to go for a run..

For biconditionals, all True instances of (Q) can only result when the condition (P) being met.

Dealing with Logic

The next step is understanding the definition of a model.

A model is an assignment of a truth value to every prepositional symbol. An example:

P: It is raining

Q: It is a Tuesday

The possible models are:

{P = false, Q = false} A rain-free day that’s not a Tuesday

{P = true, Q = false} A rainy day that that’s not a Tuesday

{P = false, Q = true} A rain-free Tuesday

{P = true, Q = true} A rainy Tuesday

A knowledge base is a set of sentences that are known to be true for all models.

P: It is raining

Q: It is a Tuesday

R: Harry will go for a run.

Example of a knowledge base:

(( Q ^ ¬ P ) → R), (Q), ¬ (P)

If it is a Tuesday and it is not raining, Harry will go for a run.

Entailment

a ⊨ b

Entailment means that in every model where sentence a is true, sentence b is also true. This is useful for asking questions to an algorithm and seeing if it is true – if we feed it in (a) our knowledge base of rules, we can ask it a (True/False) question in (b).

Consider this example:

P: It is raining

Q: It is a Tuesday

R: Harry will go for a run.

- (a) Knowledge base: ((Q ^ ¬ P ) → R ), Q, ¬ P

- If it Tuesday and not raining, Harry will go for a run.

- (b) Query: (R)

- Will Harry go for a run?

If (a) entails (b), this means that Harry will go for a run.

Method 1: Model Checking

KB ⊨ q (KB stands for knowledge base)

We check through all possible models. For every model where its knowledge base (KB) is valid/true, and its query (q) is true, we know that KB ⊨ q. Otherwise, KB does not entail q. We do not need to care about models that have a false knowledge base, e.g rainy days or Fridays for the previous example.

| P | Q | R | KB | R(Query) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| false | false | false | false | false |

| false | false | true | false | true |

| false | true | false | false | false |

| false | true | true | false | true |

| true | false | false | false | false |

| TRUE | FALSE | TRUE | TRUE | TRUE |

| true | true | false | false | false |

| true | true | true | false | true |

In this case, the row in all caps is the only instance of KB that is true, and that instance answers true for the query.

The issue is, finding all the possible combinations for models are is a time-consuming task, and for a number n of symbols we will have to iterate through 2^n different models, and a large majority of them are not valid to the knowledge base.

This brings us to another method:

Method 2: Inference by Resolution

In Computer Science, a method of proving things is done via contradiction. WE assume that something we want to prove is no true, and then show that the consequences of this logic will fall apart on itself.

One example of this: Prove that a triangle does not have two right angles.

Take a triangle T has 3 angles called X, Y, and Z. Assume that its two sides X and Y are right angles. A triangle, has a total angle of 180°, which means Z would have an angle of 0°. Z cannot be considered a corner as its angle is zero, making T not a triangle.

Back to the entailment example, to determine if KB ⊨ q:

- Check if (KB ^ ¬ q) is a contradiction.

- If so, then KB ⊨ q

- Otherwise, there is no entailment.

If KB entails q, KB and q will always be true. So (KB ^ ¬ q) returns false. Let’s revisit a question:

P: It is raining

Q: It is a Tuesday

R: Harry will go for a run.

- Knowledge base (KB) : (( Q ^ ¬ P ) → R), (Q), ¬ (P)

- If it Tuesday and not raining, Harry will go for a run.

- Query (q) : (R)

- Will Harry go for a run?

Let’s compute the logic here:

So now that we know there’s a contradiction, we can conclude that KB entails q.

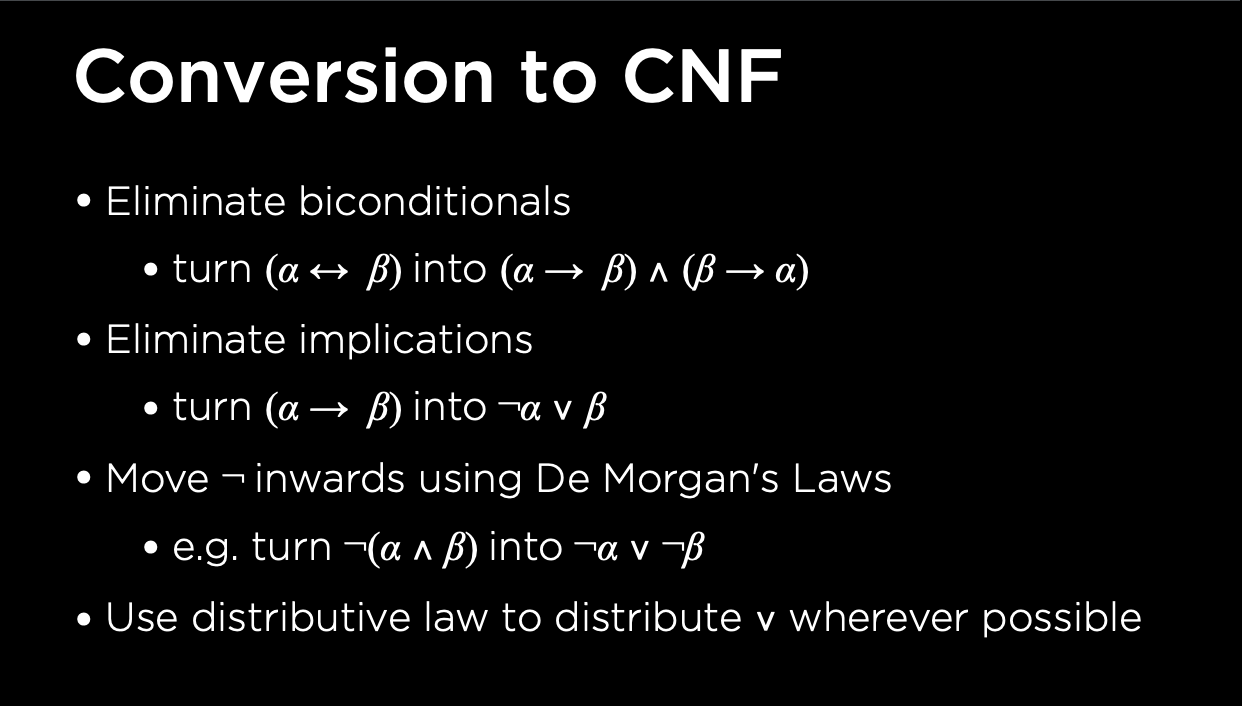

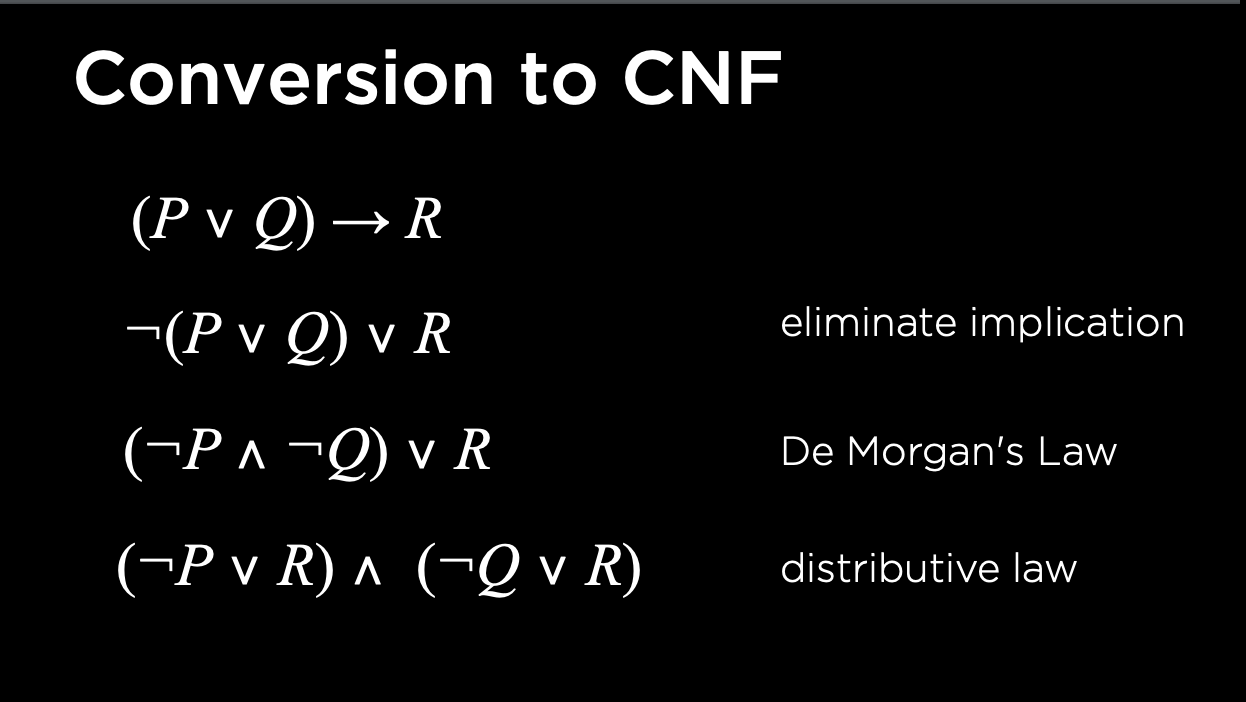

The process I did was converting the sentences in Conjunctive Normal Form. It is possible to simplify all logic into forms of AND and OR and NOT.

Before you read on, here is more terminology:

-

Clause: A disjunction of literals (symbols)

-

A disjunction means that connectives other than AND are used

e.g. (A ˅ B ˅ C)

-

-

Conjunctive Normal Form – A logical sentence that is a conjunction of clauses.

- A single sentence where clauses are all joined together with ANDs/conjunctions

-

The Empty Clause – a clause that is always a contradiction

e.g. ( P ^ ¬ P )

- The empty clause is the proof that we have a contradiction.

How do we simplify into clauses?

| Inference Method | Knowledge Base… | …Inferences from KB | Example Knowledge Base | Example Inference with Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modus Ponens | (a → b), a | b | If it’s raining, Harry is inside. It is raining. | Harry is inside. |

| And Elimination | a ˄ b | b | Harry is friends with Ron and Hermione. | Harry is friends with Hermione. |

| Double Negation Elimination | ¬(¬a) | a | It’s untrue that I didn’t write this logic. | I wrote this logic. |

| Implication Elimination | a → b | ¬ a ˅ b | If it is raining, then Harry is inside. | It is not raining or Harry is inside. |

| Biconditional Elimination | a ⇔ b | (a → b)(b → a) | If and only if it is raining, then Ron is inside. | If it is raining, then Ron is inside, and vice versa. |

| De Morgan’s Law | ¬(a ˄ b) | ¬a ˅ ¬b | It’s untrue that Harry or Ron passed the test. | Harry did not pass the test and Ron did not passed the test. |

| Distributive Property | (a ˄ (b ˅ c)) | (a ˄ b) ˅ (b ˄ c) | It rained today, Harry or Ron could be indoors. | It rained and Harry was indoors, or it rained and Ron was indoors. |

| Distributive Property | (a ˅ (b ˄ c)) | (a ˅ b) ˄ (b ˅ c) | It’s sunny today, or it rained and thundered. | It’s sunny or raining today, and it’s sunny or thundering today. |

| Resolution 1 | (p ˅ q), ¬p | q | Ron is in the Great Hall or Hermione is in the library. Ron is not in the Great Hall. | Hermione is in the library. |

| Resolution 1 (extended) | (p ˅ q1 ˅ q2 ˅…˅ qn), ¬p | q | Ron is inside or Hermione is inside or Harry is inside or Hagrid is away. Ron is not inside. | Hermione is inside or Harry is inside or Hagrid is away. |

| Resolution 2 | (p ˅ q),(¬p ˅ r) | q ˅ r | Harry or Ron is in the Great Hall, Either Hermione is in the Great Hall or Harry isn’t there. | Ron or Hermione must be in the Hall. (Think about it…Hermione must be in there, otherwise the lack of Harry means Ron should be there.) |

| Resolution 2 (extended) | (p ˅ q1 ˅ q2 ˅…˅ qn)), (¬p ˅ r1 ˅ r2 ˅…˅ rn)) | q1 ˅ q2 ˅…˅ qn ˅ r1 ˅ r2 ˅…˅ rn | Harry or Ron or Dumbledore is in the Great Hall, Either Hermione or Hagrid is in the Great Hall or Harry isn’t there. | Either Ron, Dumbledore, Hermione or Hagrid is in the Great Hall. Either Hermione or Hagrid is in the Great Hall or Harry isn’t there, so that means Ron or Dumbledore could be in the Great Hall too. |

| Empty Clause | p, ¬p | () [an empty clause with a false value] | Harry is in the Great Hall and Harry is not inside the Great Hall. | This entire sentence cannot be true because it contradicts itself. |

Here are two snippets of the CS50AI slides on how to convert sentences into CNF.

Once we can infer new clauses from what we have, we can append it it to our knowledge base with an AND connective. With those new clauses we keep trying to compare it against our pre-existing clauses and trying to infer, or ‘simplify’ them into sentences of AND and OR connectives.

Eventually, if we get the empty clause, we know that regardless of whatever values are held by the symbols, the entire knowledge base with always be false because of that one empty clause. Which causes a contradiction, proving the entailment.

Once everything has been simplified into Conjunctive Normal Form, and there is no contradiction– this means there exists an instance of symbols that proves the knowledge base true but the query false. This is not entailment.

And that concludes this very lengthy post! I hope it aids your learning, regardless whether or not you are taking this course.