Gallium nitride, also known as GaN, is a semiconductor material widely used in blue-white LED lights, TV displays, mobile phone screens, Blu-ray players, and more. However, in recent times it is starting to show its potential for revolutionizing the way circuits work, and perhaps, even replacing silicon as a more effective semiconductor alternative.

Gallium nitride crystal. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Semiconductor crash-course:

Conductors, like metals, have free electrons in their valence shells (outermost shell of the atom), that can freely flow to conduct electricity when a voltage is applied to it. Meanwhile, insulators, like rubber, have tightly bound electrons that restrict current flow (the flow of electrons produces current. Insulators do not conduct electricity readily.

And then there are semiconductors, that are insulators at a lower energy level, but turn into conductors once they reach a certain energy level. They consist of elements that contain four electrons in their valence shell, allowing each of the four valence electrons to bond with four other atoms (very nice and clean numbers behind the scenes here) creating a lattice structure.

These semiconductors are doped or made ‘impure’ by introducing other substances in a small quantity to induce instability of the electrons, causing the free movement of electrons. This instability allows the semiconductor, at a certain energy level, to conduct electricity.

(This crash course is, of course, a simplified explanation. There is a lot more happening at a deeper level! I might do another detailed post about semiconductors.)

Gallium nitride doped with magnesium. Image: Semiconductor Today

Gallium nitride doped with magnesium. Image: Semiconductor Today

Semiconductors function as transistors or ‘switches’, that need to be activated by some form of external energy to conduct electricity. This external energy provided is known as the band gap. Transistors form the backbone of processors found in all sorts of electronic devices.

A gallium nitride has a higher band gap than silicon(3.4 eV versus 1.12 eV), so it requires a greater energy level to conduct electricity. The higher energy requirement is actually an advantage, allowing GaN circuitry to be more heat resistant, with a maximum operating temperature at 300°C. A conventional, computer CPU made from silicon can only function at 80°C before the heat surroundings start to flip transistors unpredictably, causing computer glitches. CPUs run hotter when under heavy processing load, so a GaN CPU would allow it to perform at peak performance for a longer time.

GaN processors can withstand more voltage than silicon and have less resistance, so they emit less heat, making them more efficient than silicon. These properties also make GaN circuitry suitable for power electronics, for example, power adapters, inverters, battery circuits, chargers. GaN circuitry can be scaled down yet keep the performance of larger silicon circuits.

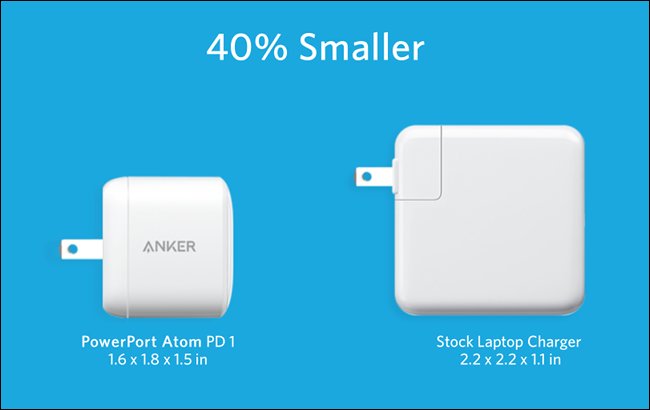

Image: Anker

Image: Anker

Partially-GaN chargers for phones and laptops are already being sold, being much more compact and about five times more efficient than conventional chargers. However, that is only scratching the surface of GaN circuitry, which could theoretically be a thousand times more efficient than silicon. Electric cars could drive farther, computers would have massive gains in processing power, and data centres would be able to cut down on carbon emissions.

The only difficulty is manipulating GaN to produce complex structures like CPUs, which are a lot more complicated than power circuits.

Image: https://steemit.com/steemstem/@jfermin70/from-sand-to-the-silicon-wafer

In CPU production, factories have to produce thin layers of crystals to be cut and fabricated into processors. Scientists still haven’t found the best way to grow GaN crystals, because their defect rate is much higher. There is even no experience yet in manipulating GaN on a nanometer-small scale. Perhaps factories will have to completely revamp the production process, which will require lots of funding and capital.

I’m hopeful that GaN technology will see the light of day - and Moore’s Law will be valid once more.

Moore’s Law? I’ll discuss that in a follow-up article.

Cover Image: https://phys.org/