Introduction [Easy to read Part 1]

A Binaural recording means recording a sound with two microphones for ‘stereo’ sound. It creates the effect of music being played in the same room as the listener. Most modern songs are recorded in stereo – if you play music with proper earphones, you can discern that some instruments are closer to the left or the right side of your ear.

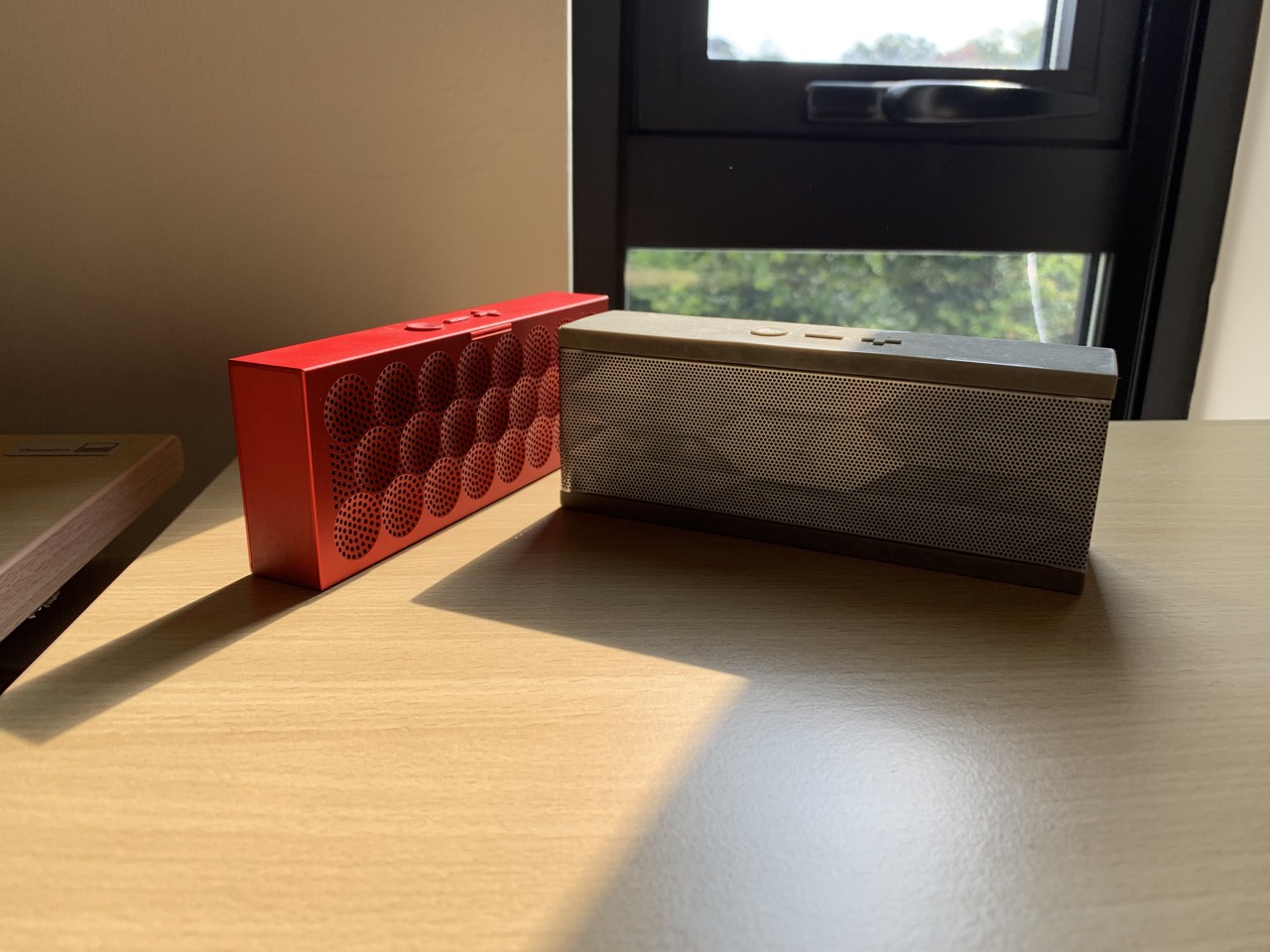

I was always fascinated with the Jambox (see first image) – arguably one of the best bluetooth speakers released in the early 2010s that sparked a trend of more portable boom boxes to come. I had both models, the original Jambox and the mini Jambox.

The latter of these two speakers had a special feature mode called LiveAudio that promised depth, detail, and “unprecedented spatial realism”. Whenever I turned on LiveAudio while listening to music, the sound suddenly became spatial – I felt that I hearing in the recording live right on front of me. 12-year old me was very impressed. This seemed to work with every song that I played, and I was extremely curious to how it worked.

(ABOVE) An advertisement for Jambox’s LiveAudio feature. Listen with earphones for the surround effect.

Let’s start from the beginning:

Mono audio: In the late 1940s, LPs, or vinyl discs originally started off as monophonic, where all the sound was recorded on a one-channel microphone. When played on a two-speaker system, both speakers would output the same audio. You can have a feel of the same effect by toggling on ‘Mono Audio’ in your accessibility settings of your smartphone or laptop. When listening to mono audio, the audio is more direct – it sounds as if you are playing it inside your head. Instruments compete for volume and space as they are layered over one another.

Stereo audio : About a decade later, stereophonic LPs began to grow in popularity. They were sold beside their monophonic counterparts at a higher price, advertising a more immersive sound. Stereo tracks mean that two-speaker systems can play different audio on each speaker. This allows mastering companies to drive different audio signals via the left and right speakers. This allows more accurate representation of live music, as instruments are usually not centred perfectly in the middle. At first, stereophonic LPs were remastered from monophonic LPs: sound engineers separated vocals to the one speaker and music to the one speaker. When listened with earphones, the effect is quite jarring as the tracks were panned to the extremes, to the point you would only hear the instruments in one side of your ear and vocals in the other.

It wouldn’t be accurate to separate vocals and instruments completely – if you were standing in the middle of a performance and heard an instrument on your left, the sound wave of the instrument would reach both ears, with your left ear hearing it louder and earlier than the right ear.

Image from gamestudiotower.files.wordpress.com

Stereo (L+R) recording soon changed that, and studios began to record music and shows with two microphones pointed away from each other. This allows the sound waves in both microphones to slightly differ from each other in loudness (amplitude) , as the recorded sounds would hit one microphone before the other based on where it originated from (delay), emulating the placement of human ears.

Most modern music is recorded in stereo, allowing us to hear instruments coming from the left and right sides of the sound space. Studios also apply post-production techniques to create a stereo effect by manipulating the delay and amplitude of sound waves in both channels.

What’s next after 2-channel sound? Surround sound, with two popular examples, the 5.1 and 7.1 surround sound variants. Created as an audio format for movies and theatres(rather than music), surround sound is rarely recorded live but added in post-production. This article won’t go into the details, but in short, surround sound relies on the placement of speakers around the listener to create a sense of direction.

Although surround sound does provide a sense of direction, humans only have two ears. Surround sound relies on physical separation of sound channels, but in the end all the sound gets picked up at two points. Surely we aren’t overcomplicating things?

Here’s the answer; it lies in biology – the human ear consists of the pinna, which is very important in human hearing! Perhaps you’ve cupped a hand over your ear to hear something more clearly. Doing this, you would notice a change in tone to the sound waves you are hearing. This is akin to holding a seashell (or a cupped hand, if you don’t have one) over your ear, creating the ‘sound of the ocean’. The pinna modifies the frequencies of the sound waves before entering your ear based on the location of its source. It ends up applying a ‘filter’ to the sound, which the brain parses to infer where the sound came from.

Image from https://www.livescience.com/52287-ear-anatomy.html

We have the third factor of variation – in stereo sound, we covered was amplitude and delay, and the third one is frequency! In human hearing, we can locate sound in three dimensions using just two points of reference. This type of hearing is called binaural hearing. Mammals with ears that use binaural hearing may have been an evolutionary need as eyesight has a limited range of view, and does not work in the dark, compared to binaural hearing.

The Technical Part 2

“Binaural” has been frequently confused as having the same meaning of the word “stereo”, caused by inaccurate semantics by marketing from recording industry when stereophonic vinyl records first came out.

The terms is still being used to wrongly label earphones in the Chinese market, especially on e-commerce sites like AliExpress.

(ABOVE) I don’t want cheap earphones! I want the good stuff!

We know from Part 1 that binaural hearing refers to using two ears to hear. Note the importance of ears as they play a part in modifying frequencies before entering the ear. The modification of frequencies can be shown as a Head-Related Transfer Function (HRTF), a response that shows how an ear receives a sound from a point in space.

When sounds are heard by the human ear they are the Head-Related-Impulse-Response (HRIR). Convoluting a sound wave with the HRIR gives converts the sound to how the listener would have heard it at the receiver’s location.

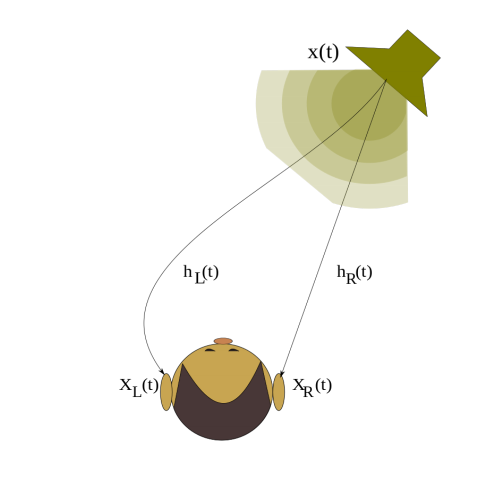

HRTF is a Fourier transformation of HRIR, a complex function defined for each ear. In the equation below, the impulse responses for the left and the right ear in the time domain as h_L(t) and h_R(t), respectively.

In the frequency domain we will denote the responses by corresponding capital letters - H_R(ω) and H_L(ω).

1 Image from the University of Ljubljana Faculty of Mathematics and Physics

Let the function x(t) describe the pressure of the sound source and let functions xL(t) and xR(t) be the pressure at the left and the right ear, respectively. In the time domain, the pressure at the ears can be written as a convolution of the sound signal and the HRIR of the corresponding ear: 1

In the frequency domain, convolution is transformed into multiplication: 1

A simplified equation:

H(f) = Output(f) / Input (f)

H(f) is the HRTF, the Fourier transformation of the HRIR.

The Output(f) is the Fourier transformation of the sound waves recorded at the ears , x(t) and the Input(f) is the Fourier transformation of the sound waves recorded at the source.

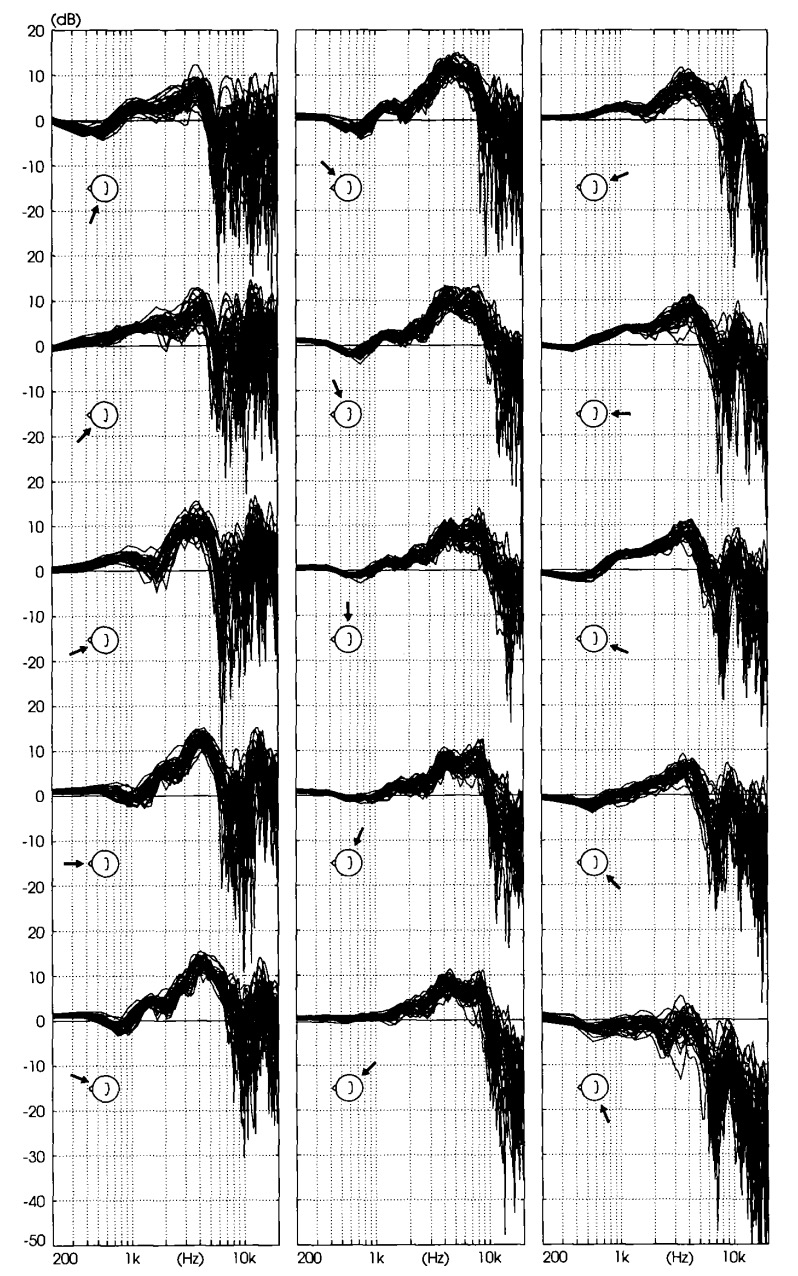

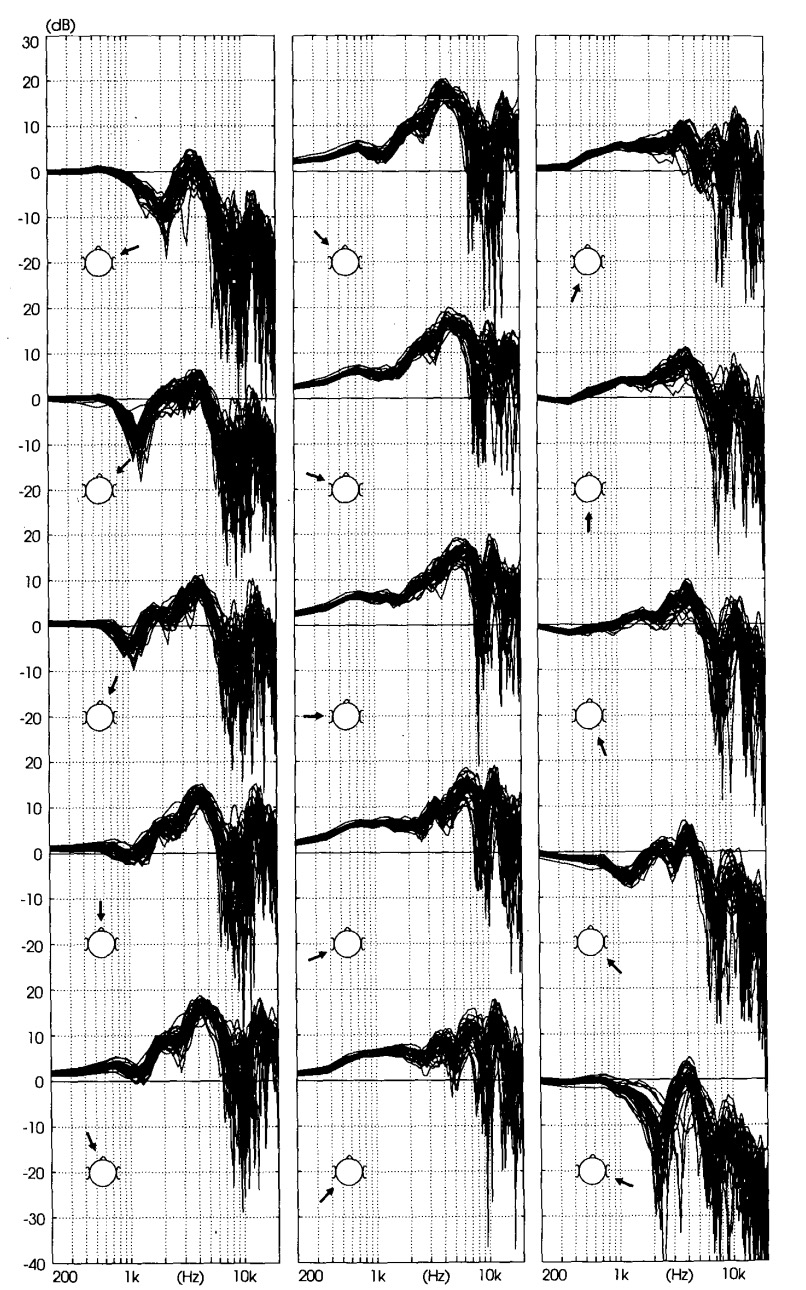

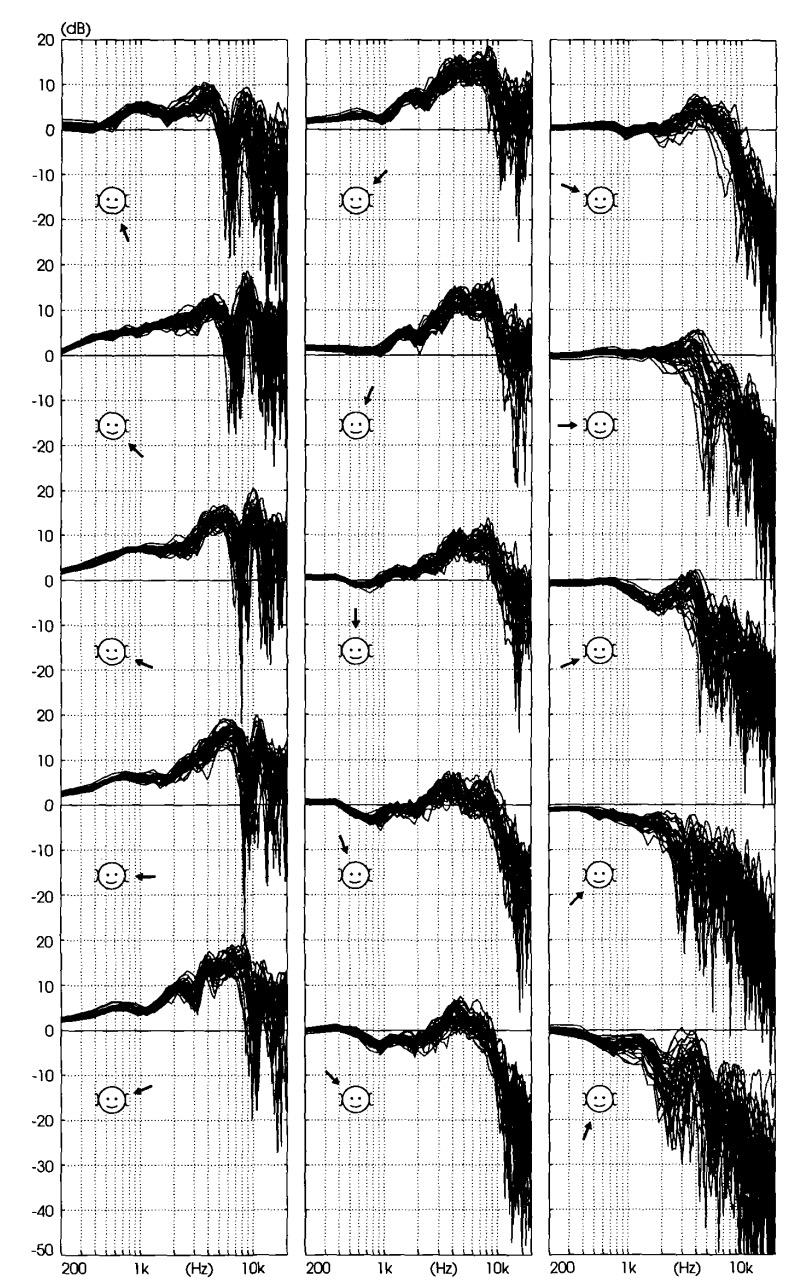

The following diagrams below are from a study by Aalborg University of Denmark, where a large group of subjects had microphones placed in their ears to record the HRIR, which was subsequently converted into HRTF using the recordings of the source, as shown in the simplified equation. HRTFs vary in every person based on their height, the width of their heads, and the size of their ears.

Regardless of varying HRTFs, they seem to have similar patterns as shown in the diagrams below.

Fig. 1. HRTFs of left ears of all subjects, covering median plane. 2

In Figure 1 it can be observed the highest amplitudes (10-15dB) are in the frequency range of 3-5KHz in the frontal directions, meaning sounds directly in front of the listener sound “sharper”. The opposite is observed for sounds from the back, where amplitudes are lower at the higher frequencies. If someone were to call your name from behind you, it wouldn’t sound as clear as someone calling your name in front of you.

Fig. 2. HRTFs of left ears of all subjects, covering horizontal plane. 2

For Figure 2, the directional variation is greater compared to the median plane in Figure 1. This is due to the shadowing effect of the head which blocks and attenuates frequencies that are coming from the right side (to the left ear, passing through the head).

The HRTFs also appear to vary more when coming from the behind (compare the second column to the third column). This is due to the ears being shaped to point towards the front rather than the back.

Fig. 3. HRTFs of left ears of all subjects, covering frontal plane. 2

The HRTFs in the frontal plane are similar to their horizontal plain counterparts, by attenuating high frequencies for HRTFs on the side opposite to the source of sound. It is observed that the HRTFs for directions above the head vary less than HRTFs for directions below the horizontal plane. This is probably why we’re good at distinguishing the source of footsteps or speech, but if someone calls us from a floor above (e.g. in a shopping mall or balcony) it’s difficult to locate the sound from above. A funny thought: maybe that’s why our ears are more adapted to hearing predators sneak up from below rather than hearing the birds fly above us.

[END OF TECHNICAL PART 2]

Applications

TL:DR; The HRTF is a function that is applied to the sound waves that enter the ear. We can calculate HRTF by placing a microphone in the human ear, record a nearby source of audio with it, and compare it to the actual source sound. HRTFs vary from person to person, based on height, head width, and the shape of the ears.

This HRTF can be reverse-engineered and applied to post-production methods to allow for true, 3-D binaural audio that allows for us to perceive direction using just two speakers. Below are some demos of binaural audio:

Back to LiveAudio, the special ‘surround’ feature in the Jambox bluetooth speaker: It was simply digital signal processing (DSP) applied to the music being played out of the speaker. It wasn’t true binaural sound, rather it was some form of HRTF being applied to enhance the stereo effect. Real binaural recordings have to be purposefully recorded with the right equipment or synthesised in post. They cannot be adapted from original stereo recordings.

Also, binaural recordings are meant to be played back on earphones, not small speakers. If the speakers are too close, their sound waves might interfere, one ear may pick up frequencies meant for the other ear (not enough separation), and your ears apply another HRTF to the audio, which biases the audio to the location of the speaker, and not the location originally encoded in the recording.

When you play back the binaural recordings on earphones, they skip the pinna of your ear and the pre-applied HRTF recording is sent straight into your ear canal, allowing your brain to properly process the locations present in the recording.

Binaural recordings are not only created in post-production – they can be created using microphones that mimic the human head and ears – these microphones are called binaural microphones, and they mimic the shape of the human ear to apply HRTF to the incoming They are commercially available, but I made my own! That’s for the next post.

-

Potisk, Tilen: Head-Related Transfer Function. University of Ljubljana., Seminar Ia - 1. year, 2nd cycle; 2015 January. Link ↩︎

-

Møller, Henrik; Friis Sørensen, Michael; Hammershøi, Dorte; Jensen, Clemen Boje: Head-Related Transfer Functions of Human Subjects. J. Audio Eng. Soc., Vol 43, No 5, 1995 May. ↩︎