Harmonics – Why Does it Sound Nice?

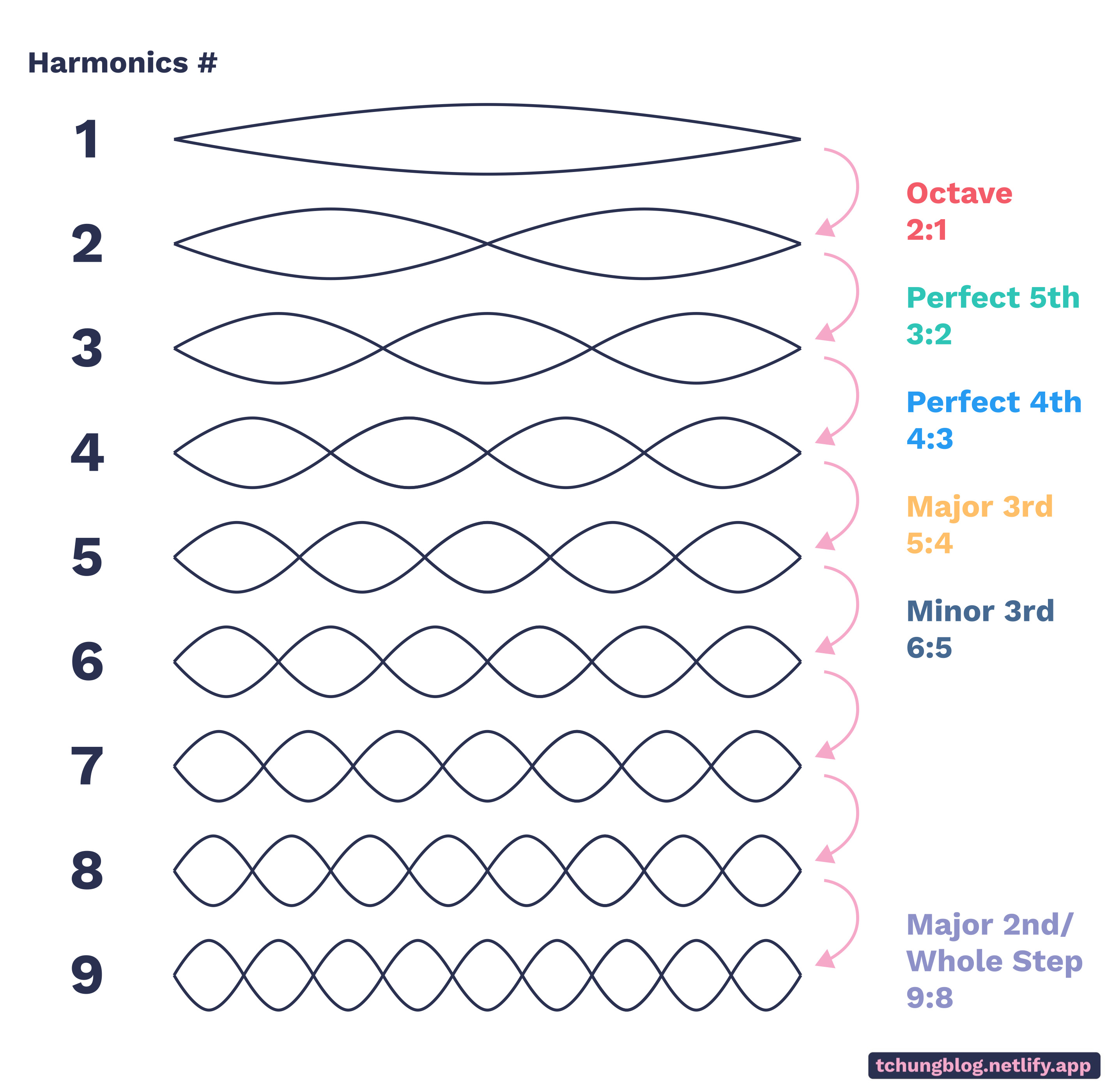

Let’s recap on the harmonic series. A string vibrates at its fundamental frequency (determined by its wavelength) usually followed by a combination of overtones at different amplitudes, which constructively interfere with the fundamental frequency.

The interference is constructive (relative to the fundamental frequency) because the wavelengths are whole number ratios of one another.

Figure 1 shows all the possible ratios using the multiples of wavelengths on a string. The ratios have been given names according to the traditional Western Scale. Each ratio represents an interval from one note to the next.

FIGURE 1

Playing any combination of the waves in the given ratios together produces the sound of perfect harmony. Here are a few examples pleasant to the ear (notes are played separately, then together):

Octave: (440Hz and 880Hz)

Perfect 5th: (440Hz and 660Hz)

Major 3rd: (440Hz and 550Hz)

Why do harmonies sound so pleasant to the human ear? Scientists believe that the brain is drawn to patterned, regular signals. Dissonance, on the other hand, causes a ‘beating’ sound [1], which is caused when two waves irregularly interfere with each other, causing a haphazard signal that sounds off-putting and discomforting.

Quarter-Step: (440Hz and 453Hz)

Tuning a Piano

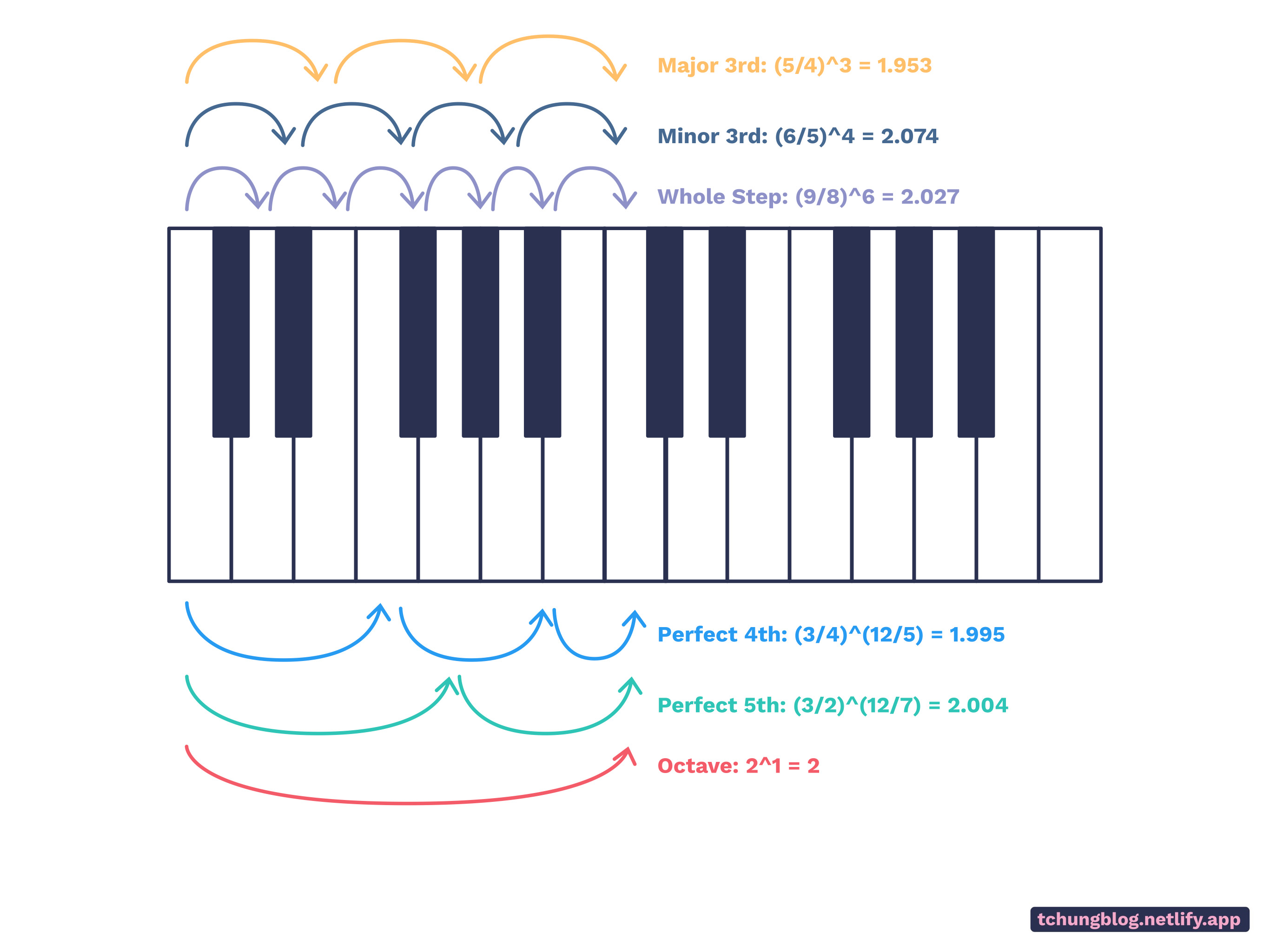

The piano has 12 keys per octave, and we need to calculate the correct frequencies for each key, and their ratios stay true to the harmonic series.

To find the frequency of a note, we multiply the frequency of the note an interval before it with the ratio of that interval. Suppose I have a note that is 440Hz. To find the Major 3rd of 440Hz, we’d multiply it with 5/4, the ratio of the Major 3rd. This gives me 550Hz, which is the Major 3rd to 440Hz. There will be multiplication aplenty as this article continues.

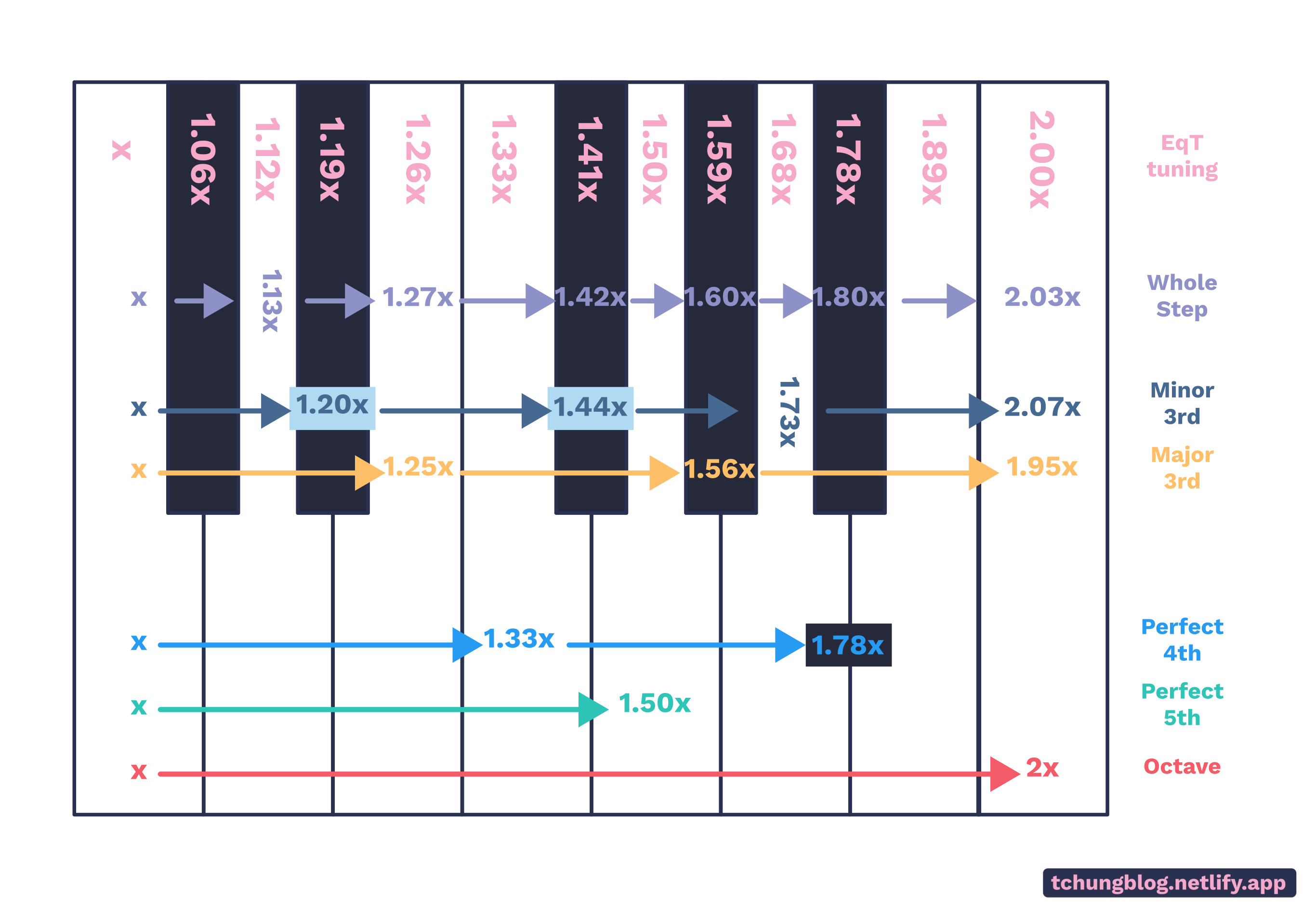

FIGURE 2

See Figure 2. Using the nice, pure whole number ratios from Figure 1. There are a few ways to theoretically to achieve this. Perhaps we could use the Major 3rd ratio (raising 4 half-steps, or piano keys) three times to climb to the next octave; or maybe the Minor 3rd (a raise of 3 half-steps) four times to get to the next octave. Besides, why not try using the whole-step six times to reach the next octave?

In fact, we can do some logarithmic math and theoretically calculate the ratios of the next octave for the Perfect 4th and 5th interval.

But something’s wrong here. An octave is a ratio with factor 2. However, we are getting all sorts of different final ratios that are pretty close to 2, but not 2. It is apparent that we cannot scale all the harmonics to meet the octave, at least using integers.

Why does this happen? The numbers were never going to look pretty anyway– because the ratios are fractions, and at some point, any frequency, no matter how large, would get divided by the ratios to form a decimal.

There is also more maths behind this – the Rational Root Theorem:

For any integers a, b, and n, and n > 1, (a/b)^n ≠ 2

This is because all roots of 2 (except the first) are irrational and cannot be represented with the fraction a/b, as a and b are rational integers.

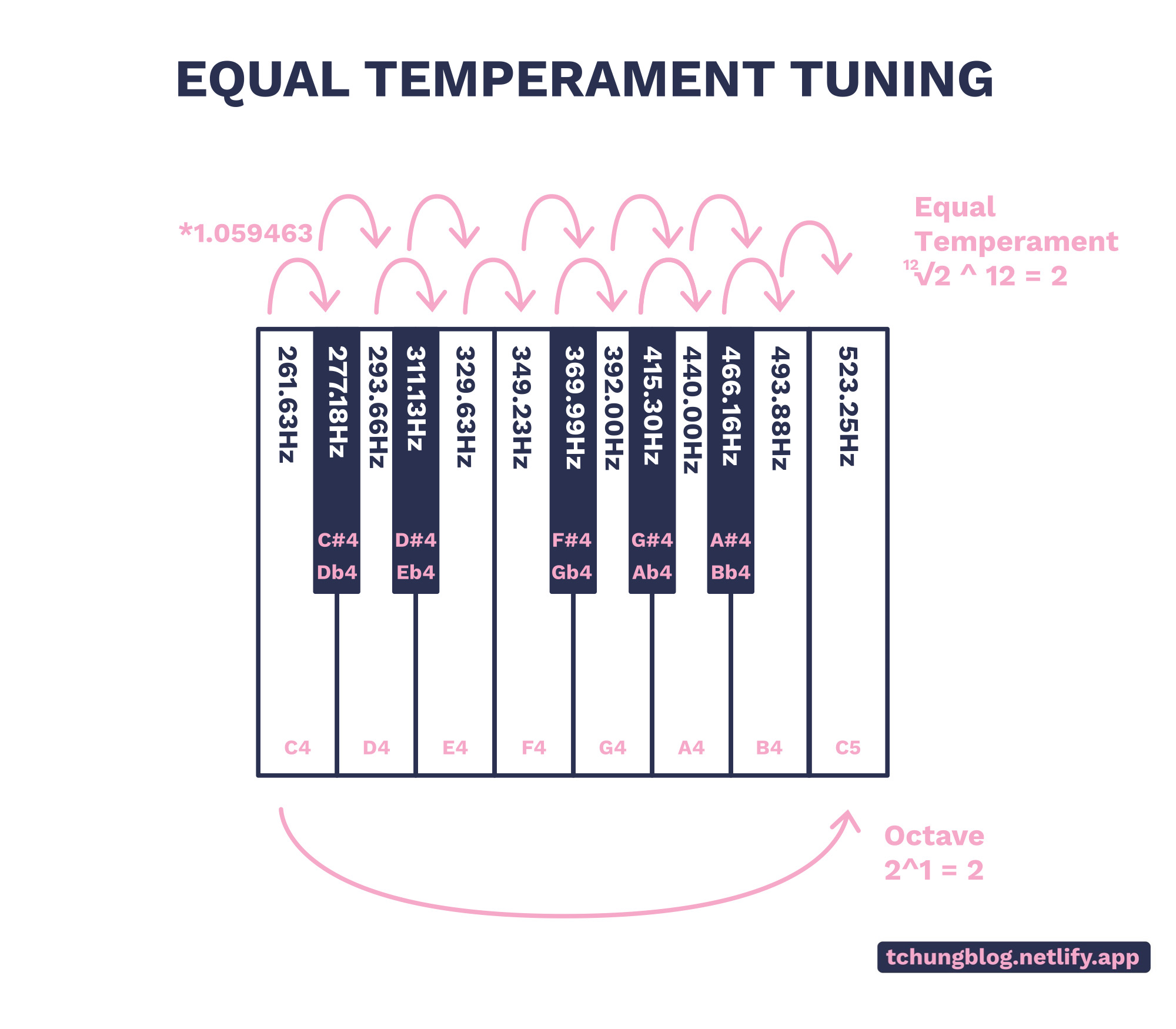

What can we do? Now, let’s introduce Equal Temperament Tuning…

FIGURE 3

(Figure 3): Nice numbers are impossible to get ahold of, so we have gone completely opposite and called upon irrational numbers to help us.

The 12-Equal Temperament is quite simple – it uses octaves as a reference point, denoting a half-step with a ratio of 2^(1/12), ≈1.05946. Since there are 12 keys in the piano, every twelve keys (octave) we have multiplied the ratio 12 times, which gives us a final ratio of x2, which is the same as the octave!

FIGURE 4

How does the 12-ET tuning compare to the other tuning methods? Figure 4 shows the ratio differences, and surprisingly, they numbers are very close! 12-ET tuning can be described as the best compromise between all tunings. This means that harmonies will not be exact, but will be a tiny bit off. The effect is negligible to the ear, although purists may disagree. A majority of modern music is composed using the 12-ET tuning, and we experience it so much in our daily lives that it doesn’t seem to stand out.

It can be said that humans prefer ratios that are sufficiently close to a rational number with a lower denominator.

Overtones are in Harmony too!

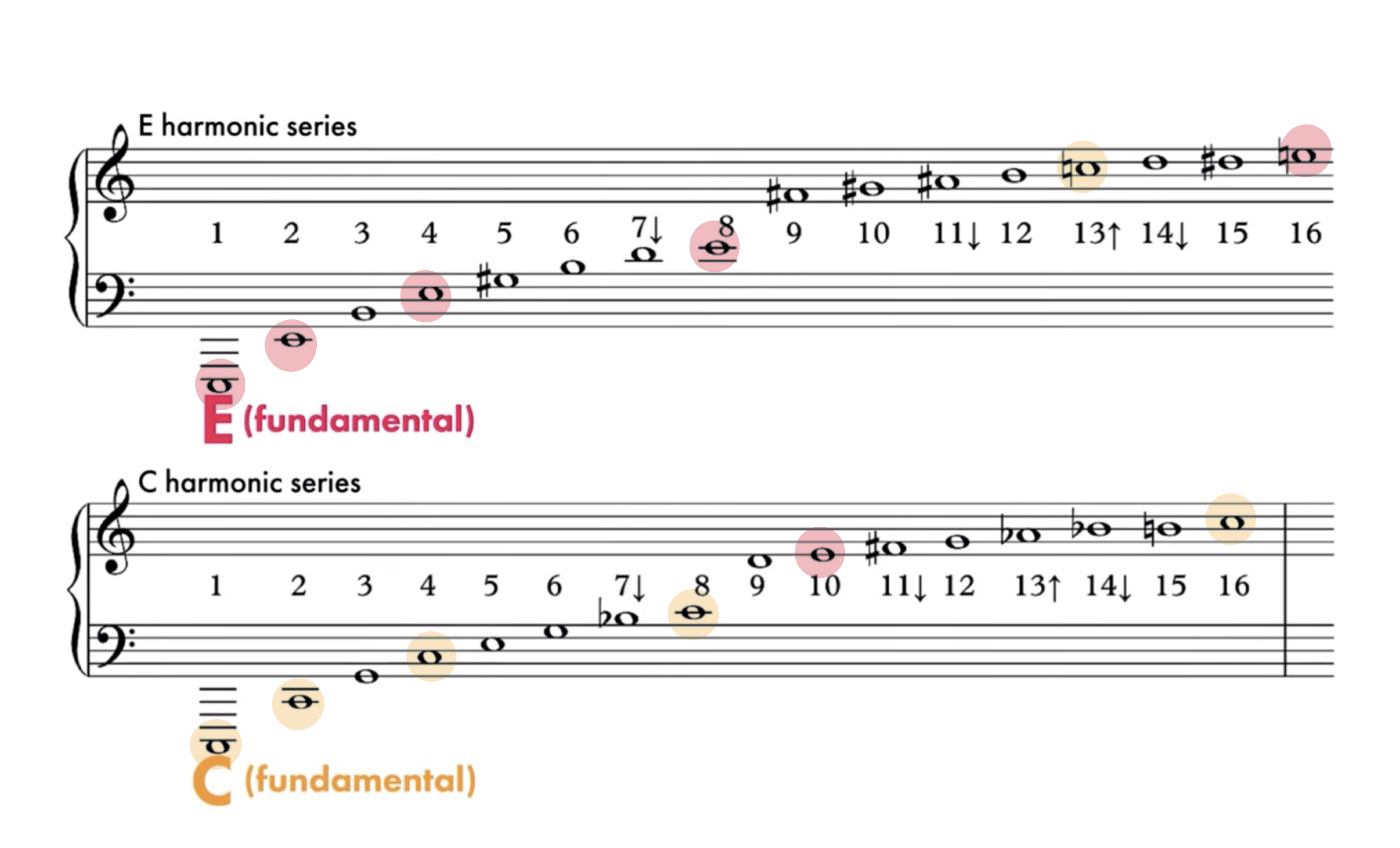

Certain notes sound nice together, not because they are (close to rational) ratios of each other, because the overtones of the notes are similar and constructively interfere with each other! In Figure 5, the notes of C are highlighted in yellow and the notes of E are highlighted in magenta. Certain overtones are shared between fundamental frequencies and they contribute to the compatibility of two notes on a piano.

FIGURE 5

(Image by Andrew Huang https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wx_kugSemfY)