Musical instruments produce sound with standing waves.

Standing waves are formed when a continuous wave is sent down a path and becomes reflected. The reflected wave is in phase and of the same frequency. as the incident wave; both waves superpose or interfere with one another, forming standing waves.

(Image from Wikipedia)

They oscillate – bounding up and down, but their profile does move in space. The standing waves alter the air pressure as they oscillate, transferring their kinetic energy to the air particles, creating a longitudinal wave of air that reaches our ears – sound.

(Image from acs.psu.edu)

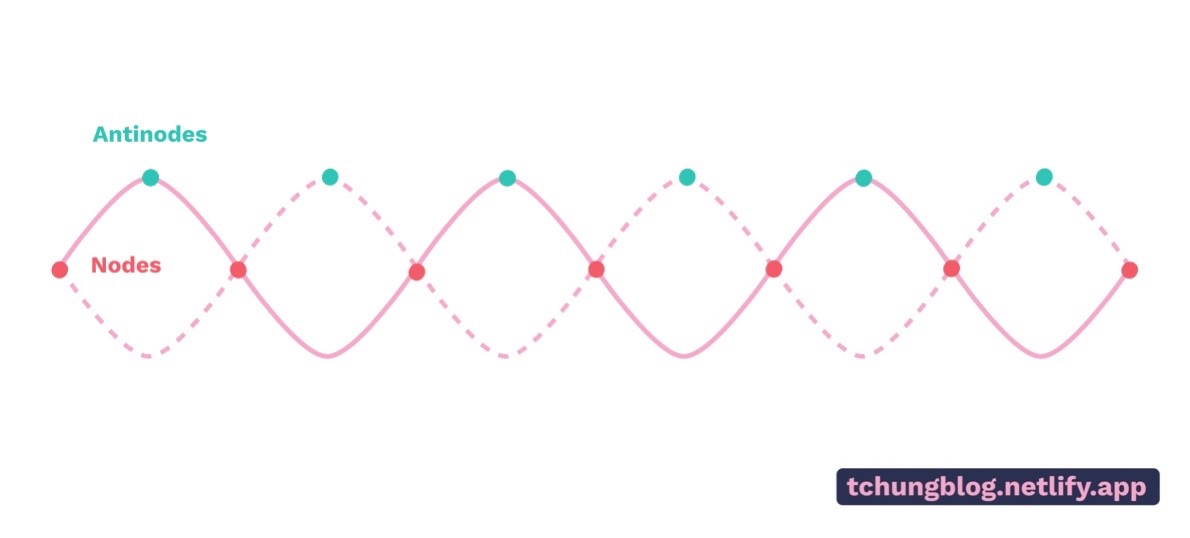

Standing waves have nodes and antinodes – the nodes are the fixed points that have zero amplitude, and the antinodes oscillate with the greatest amplitude – the forming the wave’s peaks.

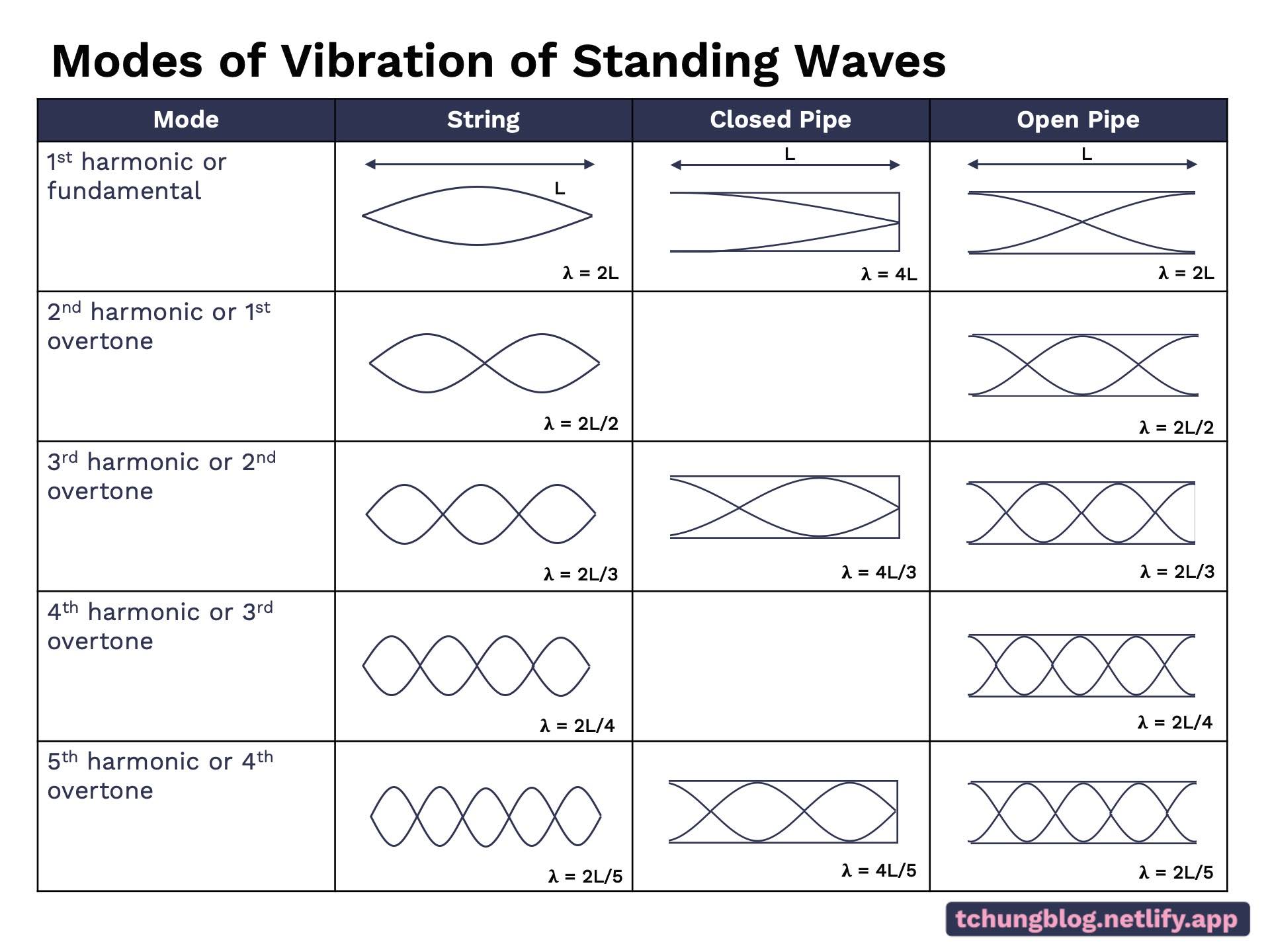

Imagine a guitar – when a string is plucked, it forms its fundamental frequency, or the 1st harmonic. It is the simplest possible standing wave. However, that is not the only frequency. Overtones are also formed in the string. They add more nodes and antinodes that are related to the fundamental frequency.

In closed strings or open pipes, the first harmonic (fundamental frequency) has a wavelength that is half the length of the string. The second harmonic’s frequency has a wavelength equal to the length of the string. The third harmonic’s wavelength would be three-halves the string’s length, and so on. Note that as the harmonics get higher, so does the frequency. Calculations are slightly different for the closed pipe as the there is an antinode at the open end and a node at the closed end.

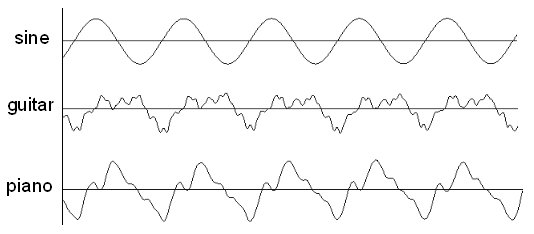

Musical instruments do not produce a pure tone upon playing; the sounds that are produced are a combination of overtones at different volumes over the fundamental frequency. This is called ‘timbre’. Different instruments will sound slightly different even though they are playing the same note. The overtones are always in a whole number ratio – i.e. quantised.

Look at the graph – it shows a pure sine tone, a guitar (being plucked five times), and a piano (being pressed five times), over a certain period of time. The guitar’s waveform is higher than the piano toward the end of the period; this is why a guitar strum sound sustains louder than the piano. The piano has a slightly earlier initial peak than the guitar, which could be attributed to the hammer action of the keys.

Despite the frequencies at over hundreds of oscillations per second, we can easily differentiate between instruments and tell that the pitches are the same. It is surprising that all these tiny differences in the overtones are easily discerned by the ears!